Mitchell and Bertie’s Evasion Story

Download the evasion story as a PDF in English or as a PDF i dansk

BACK TO THE KATTEGAT

The experiences of RAAF Navigator Flying Officer Stoney Mitchell and RAAF Bomb Aimer Pilot Officer Mervyn Bertie in Denmark

by Gail R. Michener Daughter of Stoney Mitchell

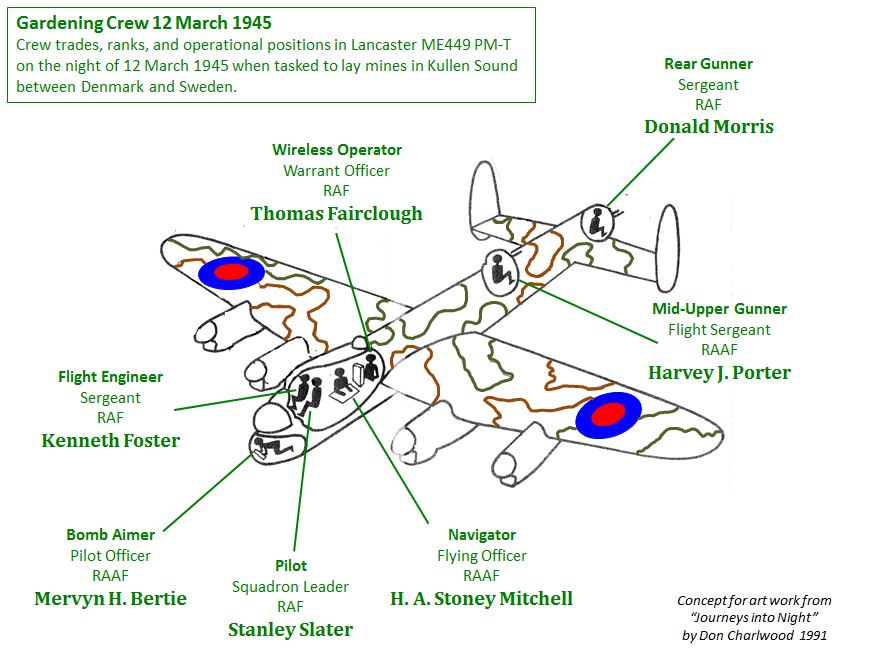

Minelaying Operation

At 1743 h on Monday 12 March 1945, Lancaster ME449, with the identification PM-T, took off from RAF 103 Squadron at Elsham Wolds, Lincolnshire, to lay mines in the sea off Kullen Peninsula where the Kattegat narrows into the northern opening of Øresund, the narrow strait that runs between Denmark and Sweden. The crew for the flight was:

| Pilot: | S/L. Stan Slater | 576 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAF | |

| Flight Engineer: | Sgt. Ken Foster | 103 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAF | |

| Navigator: | F/O. H.A. Stoney Mitchell | 103 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAAF | |

| Bomb Aimer: | P/O. Mervyn H. Bertie | 103 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAAF | |

| Wireless Operator: | W/O. Thomas Fairclough | 550 Sqdn RAF North Killingholme | RAF | |

| Mid-Upper Gunner: | F/S. Harvey J. Porter | 103 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAAF | |

| Rear Gunner: | Sgt. Donald Morris | 103 Sqdn RAF Elsham Wolds | RAF |

This crew of seven airmen had not previously flown together. Because an extra Lancaster was needed for minelaying in the Kattegat on 12 March 1945, Squadron Leader Slater was asked to make up a crew from available airmen. Foster, Mitchell, Bertie, and Porter of 103 Squadron had flown previous operations together, but their usual pilot Gaven Henry had broken his wrist several weeks previously and their usual wireless operator Keith McGinn and rear gunner John Grice had been killed on operations earlier in March 1945. In addition to the four available airmen from Henry’s usual crew, Slater found an available gunner from 103 Squadron and co-opted a wireless operator from 550 Squadron with whom he had flown previous operations.

The minelaying flight on 12 March 1945 was the 14th operation for Mitchell and Bertie, both of whom had enlisted in the RAAF in Australia in mid-1943, but it was the 57th for Squadron Leader Slater, who had joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve in Britain in late 1940. Slater had already flown two tours of 25 and 31 operations by September 1944, and thereafter primarily flew test flights for 13 Base Headquarters at Elsham Wolds.

Monday 12 March 1945 was a busy day for Bomber Command; 1108 aircraft attacked Dortmund during daylight and 19 aircraft were assigned to night-time minelaying in the Kattegat. When the minelaying bombers were detected heading east over Denmark, two Junkers nightfighters were activated from Staffel 3 of I./NJG 3 based at Fliegerhorst Grove near Karup in Jutland, Denmark. Hauptmann Eduard Schröder, pilot of Ju88 D5 + AL with flight engineer E. Brunsendorf, and radio operators T. Hessenmüller and W. Zeinert, downed two returning bombers near the Danish island of Samsø at 2116 and 2127 h with the loss of 13 of the 14 crew members.

ME449 Attack and Crash

Schröder was then directed to another returning Allied bomber. At 2145 h on 12 March 1945, just as Lancaster ME449 was approaching the North Sea on the western coast of Jutland, cannon fire from Junkers Ju88 D5 + AL damaged the aircraft and ignited a fire in the starboard wing that flared up again after several attempts to extinguish it. Slater turned the Lancaster back over land and gave the order to abandon the aircraft. Gunners Porter and Morris did not survive the German cannon fire and the subsequent crash, but the other five airmen parachuted from the burning aircraft one by one, and all landed with minimal injuries.

Eduard Schröder, pilot of Junckers Ju88 D5 + AL on the night of 12 March 1945.

By war’s end, Schröder was credited with a total of 28 combat claims (5 day and 23 night).

In civilian life Schröder was a dentist.

Image source: C. Petersen 1993 “Tyske Fly i Danmark 1940-45 Bind II Natjagere” p. 87.

Lancaster ME449 belly landed in Svend Jensen’s farm “Østergård”, located 3.9 km NE of Lyne, and broke into three pieces. The bodies of Harvey Porter and Donald Morris were quickly retrieved from the damaged Lancaster by four members of the local Civilbeskyttelse (CB) and taken to Tarm Sygehus where they were washed and again dressed in their uniforms. By this stage of World War II, Germans were no longer holding military funerals for Allied combatants and instead hurriedly buried bodies wherever they fell. When the Germans stationed in Tarm realized that two Allied airmen from the downed aircraft were in the mortuary of the hospital, they demanded that the uniforms be removed and the bodies placed in sacks. Rather than returning Porter and Morris to the crash site for burial, the Germans arranged for the bodies to be taken on a cart to a plantation on the edge of the Tarm and unceremoniously thrown into a shallow grave. A funeral service was held five months later, on 12 August 1945, and the site, by then with engraved memorial stones and known as Englændergraven, was consecrated.

Englændergraven.

The burial site of Harvey Porter and Donald Morris on Østermarksvej, near Tarm, Jutland, Denmark.

Photograph by Gail R. Michener 12 June 2011.

German soldiers salvaged parts of the crashed Lancaster, but even decades later locals still found pieces of ME449 scattered around the crash site.

Remnants of ME449.

Hans Vestergård showing Gail Michener, daughter of Stoney Mitchell, pieces of ME449 that he collected from the crash site after the war.

Photograph by Dan Michener 16 June 2013.

Evasion

The five airmen who had parachuted safely from ME449 now faced the task of evading the German occupiers of Denmark. As part of their Bomber Command training, airmen attended Escape and Evasion Lectures, and they received specific information about what to expect depending on the country in which they landed. Long before March 1945, the majority of Danes were sympathetic to the Allied cause so evaders (combatants who elude capture) and escapers (prisoners who break free from enemy control) had a high probability of receiving assistance from Danish civilians. Additionally, the Danish Resistance had become well organized, and those airmen who made contact with Resistance members could expect their route to safety to be coordinated by Resistance members.

By lucky chance, three of the five surviving airmen immediately received shelter with Danish civilians who had contacts with members of the local Danish Resistance. Within a few days, Stan Slater with Thomas Fairclough and later Ken Foster were all guided through Danish escape lines via Fredericia and Copenhagen to Sweden. Mitchell and Bertie had a more exciting experience.

Stoney Mitchell and Mervyn Bertie were the second and third men to bale out of Lancaster ME449, after Ken Foster but before Thomas Fairclough and Stan Slater. The exact locations at which Mitchell and Bertie landed are not known, but shortly after baling out they found each other in the darkness, buried their parachutes, removed insignia and brevets from their clothing, and spent the first night sleeping outdoors. Although near the North Sea on the west coast of Jutland, Mitchell and Bertie knew that safety lay in reaching neutral Sweden on the east side of Denmark. With the aid of a compass and a map from their RAF-issued escape kit, Mitchell and Bertie planned to walk across Jutland in a north-easterly direction to reach a port from where they could find passage across the Kattegat to Sweden. Their intended goal was Grenaa, about 200 km from their parachute landing site.

Help from Danish Civilians

The next day, 13 March 1945, when 21-year-old Dorthea Kristensen saw Mitchell and Bertie walking northward along Vejlevej towards Tarm, she suspected that they were Allied airmen from the aircraft she knew had crashed the previous night. Kristensen approached them and, knowing that Germans were stationed in Tarm, she indicated that they should turn back. Dorthea Kristensen led them to the nearby farm house of her parents, Maria and Kr. Peder Kristensen. Although none of the Kristensens spoke English, the family provided food, comfort, and protection for the two Australian airmen, including a place to sleep in the attic. Next morning, the Kristensens recommended a route for Mitchell and Bertie to take on their journey across Jutland. As a memento for their assistance, Merv Bertie gave his flying gauntlets to Peder Kristensen; 66 years later, Kristensen’s daughter Dorthea Madsen handed those gauntlets back to Bertie’s daughter Susan Westcott.

Sue Westcott, daughter of Merv Bertie, with the flying gauntlets that her father had given to Peder Kristensen in 1945 and which were returned to her in 2011 by Kristensen’s daughter Dorthea Madsen.

Dorthea Madsen also returned the rosette made from the shoulder braiding removed from the airmen’s uniforms.

Photograph by Dan Michener 12 June 2011.

Mitchell and Bertie continued on foot in a north-easterly direction for about 90 km over the next three days, finding food, shelter, and advice from various Danes along the way. The locations and identities of the famers who protected Mitchell and Bertie on the nights of 14/15 and 15/16 March remain unknown, but from 16 March onwards the evasion route is well documented.

Towards evening on 16 March 1945, Stoney Mitchell and Merv Bertie sought help at “Sejlgårdsmark”, the farm of Åge and Ottine Fisker near Funder. With the assistance of a couple of local English speakers, carpenter Maylor Ambrosiussen and teacher Nørby Christensen, the two Australians were able to explain who they were. Now they were in luck. Åge Fisker knew how to make contact with the Danish Underground because his oldest son Søren Fisker worked as a herdsman for brothers Sigurd Birk and Gunnar Birk, who were members of a Resistance group. After dinner with the Fisker family, Mitchell and Bertie were safely hidden for the night in the hay barn.

“Sejlgårdsmark” Fisker family farm near Funder in the 1940s. Home of Aage and Ottine Fisker who protected Mitchell and Bertie on the night of 16/17 March 1945 and helped put the two airmen in contact with the Danish Resistance.

Original image in the private collection of the Fisker family photographed by Gail R. Michener.

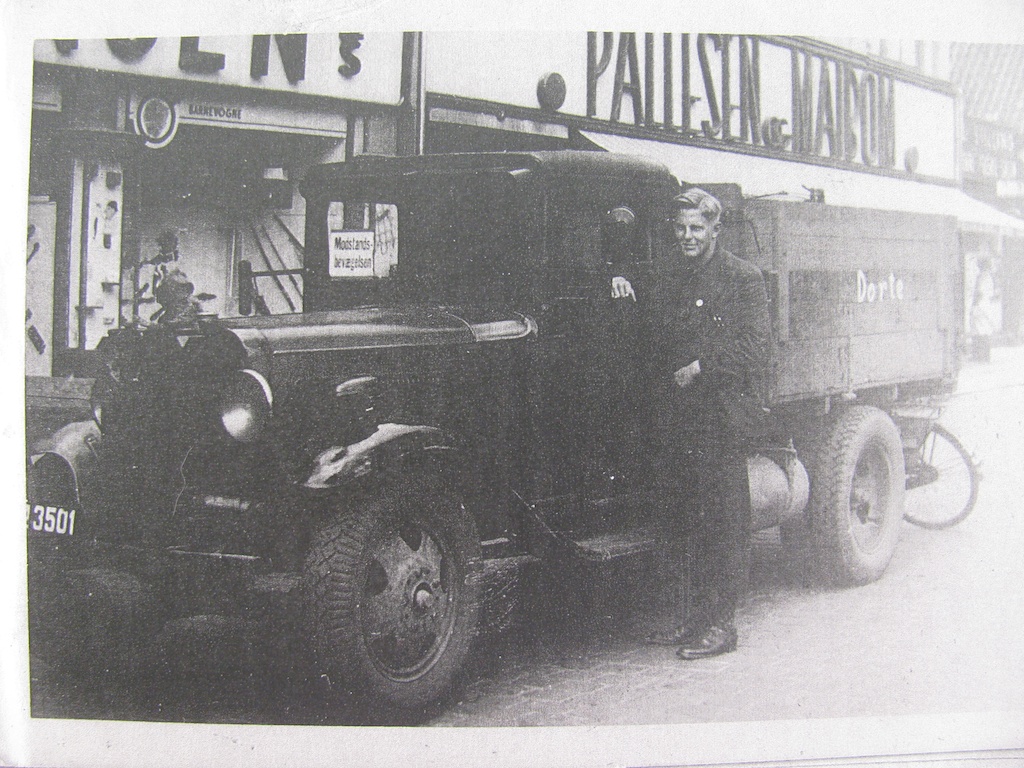

In the early morning of 17 March 1945, Åge Fisker sent a message to the Birk’s farm “Frisenborg”, located on the south side of Ikast, around the time that the Ikast weapons-receiving group operated by Ole Engberg returned to the Birk farm after waiting fruitlessly at Isenbjerg for an expected drop of weapons from the Special Operations Executive (SOE). On learning of the two Australian airmen at Funder, Ole Engberg and Gunnar Birk drove in Engberg’s truck, nicknamed “Dorte”, to Fisker’s farm where Engberg looked for the Australians in the hayloft, and on seeing them said “Welcome to Denmark” in English. Engberg quizzed Mitchell and Bertie to assure himself that they were genuine Allied airmen before driving them from Funder to a safe house in Ikast.

Ole Engberg with the truck “Dorte”.

Engberg drove in the guise of a lignite worker when gathering supplies dropped by the SOE and when transporting Mitchell and Bertie between safe houses.

Help from Danish Resistance

Engberg took Mitchell and Bertie to the home of Arnold Petersen and his wife Naomi (nee Lind) on the northwestern edge of Ikast. Arnold Petersen was also a member of the Ikast weapons-receiving group and, like Engberg, spoke excellent English. After a career as a sailor, including a period in the U.S., Petersen settled in Ikast in 1937 where he pursued a lifelong career as an artist. The room in which Mitchell and Bertie stayed for 5 days overlooked “Sandhus”, the farmland of Naomi’s family. After the war, Petersen painted that view in oils and sent it to Stoney Mitchell in Australia where it hung in an honoured place in the Mitchell home and now is part of the Canadian home of Mitchell’s daughter Gail Michener.

Oil painting by Arnold Petersen.

The view seen by Mitchell and Bertie while hidden in the Petersens’ house near Ikast.

Original painting in Gail Michener’s private collection.

From Ikast, Ole Engberg took Mitchell and Bertie to the home of businessman and Resistance member Alfred Balle Pedersen and his wife Magdalene (nee Jensen Bjerre) in Herning. Here they remained for 12 days, mostly in an upstairs room, but occasionally they were taken down to the main-floor living room from where the two Australians could view the activities of the Germans stationed across the road. Two other people lived in the Herning safe house, the Pedersen’s 5-year-old son Poul Helge Pedersen and Helge’s aunt Frida, sister of Magdalene. None of the Pedersen family spoke English, but various Resistance members visited and one night Ole Engberg took Mitchell and Bertie to the house of his cousin Louise Zeuthen so the Australians had opportunities to converse in English with local Danes.

In addition to the rooms in which the two Australians stayed in Ikast and Herning, both safe houses had secret compartments where people could be hidden if the house was at risk of being searched. Fortunately these secret locations, under the flooring of the main level in the Petersens’ house in Ikast and under the eaves of the attic via a crawl space in the Pedersens’ house in Herning, were not needed during the period Mitchell and Bertie were in residence. From time to time during the Occupation, the Pedersens also protected Danes who were potentially at risk of arrest by the Gestapo.

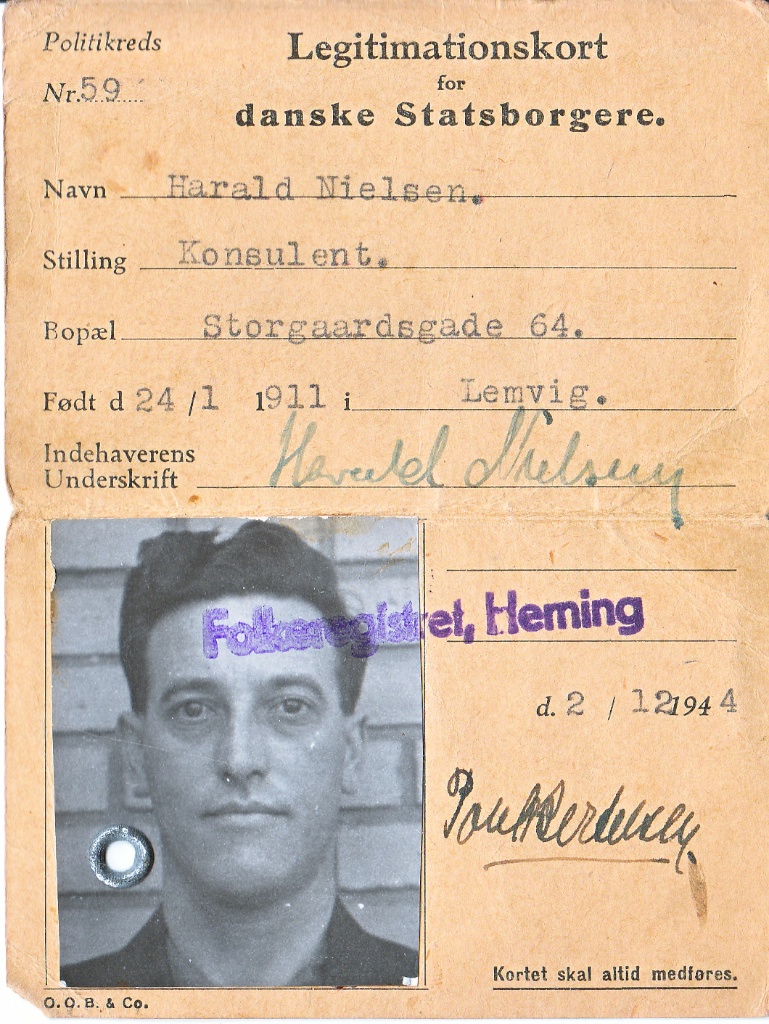

Photographs taken in the garden against the back wall of the Pedersens’ house in Herning were used to make counterfeit identity cards with fictitious information, except for the birth dates. Importantly, Mitchell and Bertie needed to be confident with their Danish names, Peter Nielsen for Mervyn Bertie and Harald Nielsen for Stoney Mitchell (whose first name was Harold, though he preferred his third name Stoney)

False identity card for Stoney Mitchell.

The photograph was taken against the back wall of Alfred Balle and Magdalene Pedersen’s house in Herning.

Original document in Gail Michener’s private collection.

On the night of 2 April 1945 (Easter Monday), Anton Jens Toldstrup, leader of the Jutland weapons-receiving group, took Mitchell and Bertie by car from Herning to Ebeltoft. Along the way, near Aarhus, the car was stopped by Germans who demanded identity cards but eventually let the group continue when Toldstrup asserted his apparent authority as an officer of the Statens Civile Luftværn (National Civil Air Defence) in a hurry to attend a meeting.

Toldstrup

Anton Jensen, better known by his Resistance name Toldstrup, in the disguise of an officer of the Statens Civile Luftværn.

Image source: S. O. Gade. 2011. “Toldstrup en biografi om en modstandshelt” p. 51.

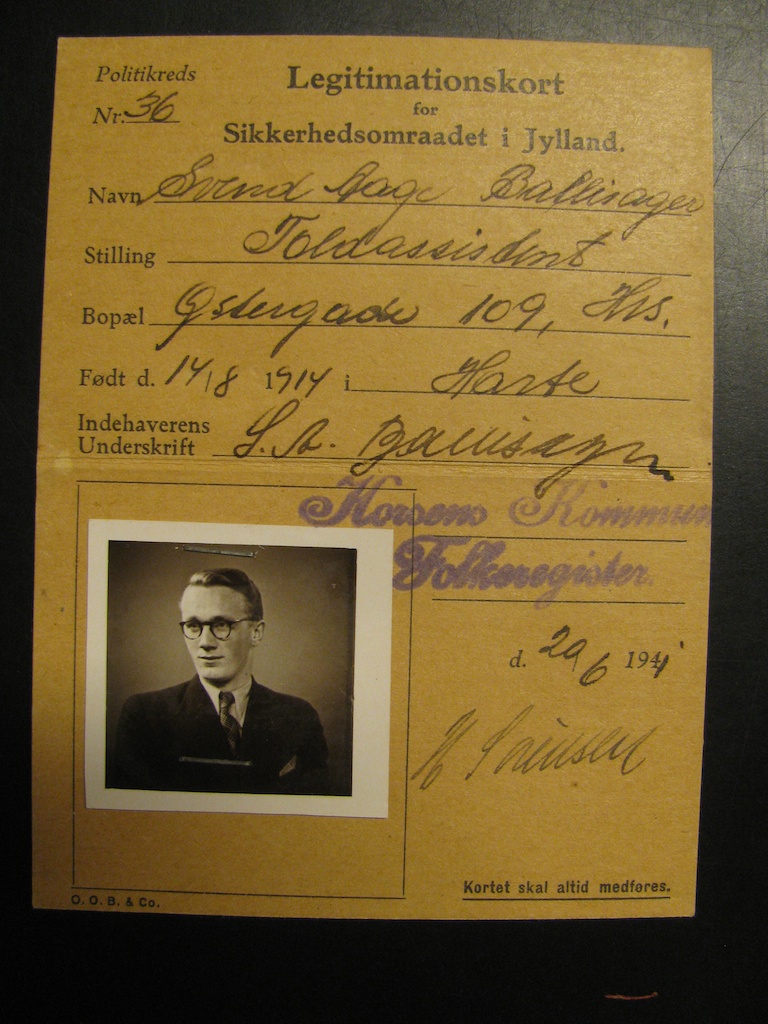

In Ebeltoft, Mitchell and Bertie stayed for 2 days with customs officer Svend Åge Ballisager, his wife Gudrun, and their 3-year-old daughter Sine Marie. Gudrun spoke more English than her husband and she played cards with Mitchell and Bertie while they waited for news of a vessel to take them to Sweden. Ballisager took advantage of his post as a customs inspector in Ebeltoft to work for the Danish Resistance smuggling people, armaments, and goods between Denmark and Sweden.

Official identity card of Svend Aage Ballisager.

Original document in Ebeltoft Byhistoriske Arkiv photographed by Gail R. Michener 20 October 2011.

Late on Wednesday 4 April 1945, Mitchell and Bertie were driven to Øerhage, 6 km south of Ebeltoft, where they used the suspension bridge to the stone and gravel silo operated by Aarhus Sten og Grus Kompagni to reach the boat “Freden”. Although registered in Svendborg as fishing vessel SG166, “Freden” was owned by the Jutland branch of the Danish Resistance under the code name “SP100” and operated with the crew of Ulf Henrik Svendsen-Tune, Henrik Henriksen, and Johannes Rasmussen by Dansk Hjælpetjeneste out of Göteborg. Toldstrup regularly communicated via telegram with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) about shipments of armaments and personnel traveling between Denmark and Sweden on “SP100”, and on 4 April he sent a telegram saying “The 2 Australian airmen will go to Sweden by S.P. 100 next time”.

Fishing boat “Freden”

“Freden” smuggled armaments, goods, and people between Denmark and Sweden from mid-March to mid-April 1945.

The original photograph in Gail Michener’s private collection does not identify the persons on board or the date.

Crossing the Kattegat

Mitchell and Bertie assisted with unloading smuggled armaments before “Freden” left Denmark for Sweden in the early hours of 5 April 1945. Thus, 24 days after they had dropped mines by air in the Kattegat, Stoney Mitchell and Mervyn Bertie crossed the Kattegat by water, arriving in Göteborg later that day. They reached Stockholm by train on 7 April, then flew on the night of 15-16 April to Leuchars, Scotland, on BOAC courier plane Dakota G-AGGI. Mitchell and Bertie were de-briefed by Military Intelligence in London, assigned leave, and did not return to 103 Squadron at Elsham Wolds until May 1945, by which time the war had ended.

Last Lancaster Flight

Stoney Mitchell and Merv Bertie did fly one more time in a Lancaster. After hostilities had ended, RAF airmen and ground crew were given the opportunity to take a “sight-seeing” tour over some of the bombing targets to observe the damage that had been caused by Bomber Command operations. On 31 May 1945, Stan Slater piloted a flight over Heligoland, Cuxhaven, Hamburg, Brunswick, Kassel, Mohne Dam, Central Ruhr (Dortmund, Wanne Eikel, Gelsenkirchen, Oberhausen, Essen, Duisburg, Dusseldorf), and Cologne. In addition to Slater, Mitchell, and Bertie, the sight-seeing “crew” for the 6 hour 15 minute flight included six other aircrew, two ground crew, and a WAAF driver.

Sightseeing crew 31 May 1945.

Three aircrew who survived the crash of Lancaster ME499 on 12 March 1945 were part of the sightseeing tour over Germany in Lancaster ME551.

Merv Bertie second from left in front row; Stoney Mitchell fourth from left in front row; Stan Slater fifth from left in back row.

Original photograph in Gail Michener’s private collection.