Escape and Evasion Advice

On each operation over enemy territory, air crews were issued with items to assist them in evading capture should they be forced to land in enemy-occupied countries or within Germany itself. The basic items included aids boxes, compasses, and map packs and purses appropriate to the territory in which crew might land. The aids box contained items such as Horlicks tablets, glucose sweets, water bottle and water purification tablets, fishing line and hook, matches, and razor. In the March 1945 update of the M.I.9 Bulletin, the purse issued for operations over Denmark was “Black Purse 43” containing map F.G.S. A for Norway, map F.G.S. E for Denmark and southern Sweden, and Norwegian and Danish kroner. Although 150 Danish kroner was the intended amount of currency, a note in the Bulletin (chapter 2 , p. 1) states “The Danish currency for Black Purses is in very short supply, and only a very limited number of these purses is available for issue.”, and p. 2 indicates the available amount available as Kr 50. Air crew were also advised to carry a photograph suitable to be used in a false ID card. By March 1945 such photographs were no longer being made at the Operational Training Unit stage of training, so airmen were given recommendations on suitable attributes when getting their own photographs made. Advice included “Subjects must look tidy but not ultra smart.” and “Try not to look as if you are “Wanted”.” Other information included the dimensions of photographs for ID cards in various countries.

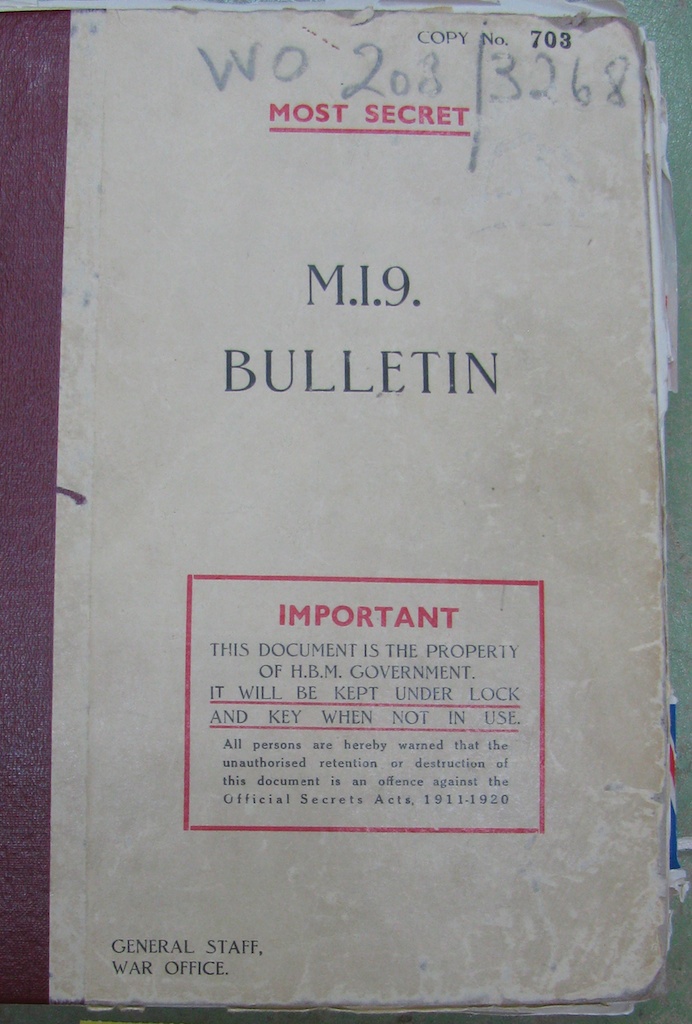

MI9 Bulletin.

MI9 Bulletin.

Photograph of original document held in The National Archive, Britain.

MI9 recommendations for behaviour after baling out included quick burial of the parachute so as to obscure the landing location from the enemy, making minor alterations to clothing to more closely resemble civilians, and not arousing suspicion by acting furtively. MI9 also noted that “if the descent has been made at night, well away from the aircraft, and the parachute is effectively hidden, the enemy have no focal point on which to base their search. Therefore the evader can seek help earlier, without having to hide for three days”, the latter being the recommendation for those exiting aircraft after a conspicuous crash landing.

After baling out

Merv Bertie and Stoney Mitchell observed the advice they had been given in Escape and Evasion lectures. Writing his memoir “Experiences in Denmark” 32 years later, Merv Bertie recalled that when he and Stoney Mitchell found each other on the night of 12/13 March “ we both composed ourselves after recognition and decided to bury the chutes … We had our escape map of Denmark, rations and Compass and decided to walk by the compass to the East Coast of Denmark, steal a fishing boat and make for Sweden. We then removed our rank and brevets from battle dress and as we were both wearing heavy jumpers underneath, these were taken off and put on over our battle dress. Stoney was wearing ordinary shoes and I had flying boots on, so pulled my trousers over the boots to hide them as much as possible.”

Finding food

The aids box issued to each crewman contained limited nutritional items, so the necessity to seek food would soon become paramount when on foot in cool spring weather. Mitchell and Bertie were lucky in that every Danish person they approached did provide some food, even if unable to offer shelter.

Of their first day of walking, 13 March 1945, Bertie recalls in his memoir “We called at a farm house and by signs, asked for food and drink from a lady who appeared very frightened (probably from the look of us and fear of the Germans for helping escapees) however she gave us a drink of sour milk and some food and we proceeded on our way.” Later that day Mitchell and Bertie were helped by Dorthea Kristensen who took them to her parents’ farm house where they washed up, were served as much food as they could eat, and, in the case of Mitchell, obtained cigarettes using the Kr 50 from the aids purse.

For the next day, the only mention of food that Bertie makes in his memoir occurred in the evening when the two Australians “called at a farm house we could see a short distance away. This farmer was a little wary of us but took us in where we washed and were given food and cigarettes. He permitted us to stay that night, provided we slept in the hay shed”. The following day, 15 March 1945, “we met a Danish worker on a bicycle, going to work on a farm. He could speak good English and insisted that we take his packed lunch”. After following that man’s advice to by-pass a nearby town, Mitchell and Bertie eventually “called at another farm house, given food and slept in the barn.”

Recalling their fourth day of walking, 16 March, Bertie reports that “just on dark we called at a small farm house and asked for food, the farmer’s wife, who came to the door, started crying and was very frightened, so we accepted the eggs she gave us and moved off”. Later, at another farm house, they “were taken in, allowed to wash and clean up and given a very good meal and some cigarettes.” Mitchell and Bertie were now at the farm of Aage and Ottinne Fisker near Funder, and from hence forward all their needs were taken care of by Danes who were members of the Resistance or who had contacts with Resistance members.

Resistance assistance

In his “Experiences in Denmark”, Bertie reports that while they were at the Fisker Farm on the night of 16/17 March, “some men arrived and asked all sorts of questions and at times appeared anything but friendly. They examined our clothes, watches, identity cards and all we possessed and said they would see us the next day … Early the next morning the ‘Big Boss’ returned with a truck and other men and we were given civilian clothes and stripped of everything else.” In their MI9 debriefing report, Mitchell and Bertie specified “they removed everything with British markings, Air Ministry watch etc., and gave us civilian clothes and shoes.”

The men who arrived in the evening at the Fisker farm were presumably carpenter Maylor Ambrosiussen and teacher Nørby Christensen, both of whom spoke English. In a letter written from England in early 1946, Mitchell thanks Nørby Christensen for “taking possession of the watch” and asks Christensen to keep it until his return to Australia. The uniforms were buried by Aage Fisker in a field in a potato cooker that was dug up as soon as Denmark was liberated in early May. The fate of the uniforms has been lost in the mists of time, but Fisker’s second son Poul recalled in 2012 that he wore the boots after they were re-soled. The “Big Boss” who came next morning was Ole Engberg, leader of the Weapons Reception group in the Herning district. Engberg was accompanied by Gunnar Birk, a Resistance member from Ikast.

Apparently Mitchell and Bertie still had some RAF-issued items when they reached Arnold and Naomi Petersen’s safe house in Ikast. Writing to Merv Bertie’s daughter Sue Westcott in 1988, Arnold Petersen recalled that “We were told to burn all what they wore and … belongings and had to do it while they were looking at it – and we burned it in the kitchen range – uniforms – underwear – all of it – and there I cheated and hi[d] away a tiny compass – the size of an american ten cent piece”.

While staying at the next safe house in Herning, Bertie recalls that “we were dressed up and a photographer arrived to take photos in preparation for Danish identity cards. We were both given Danish names and asked to practice signing the name. I was first allotted Nils Nielsen which was later changed to Peter Nielsen as I was more consistent with the latter signature.”

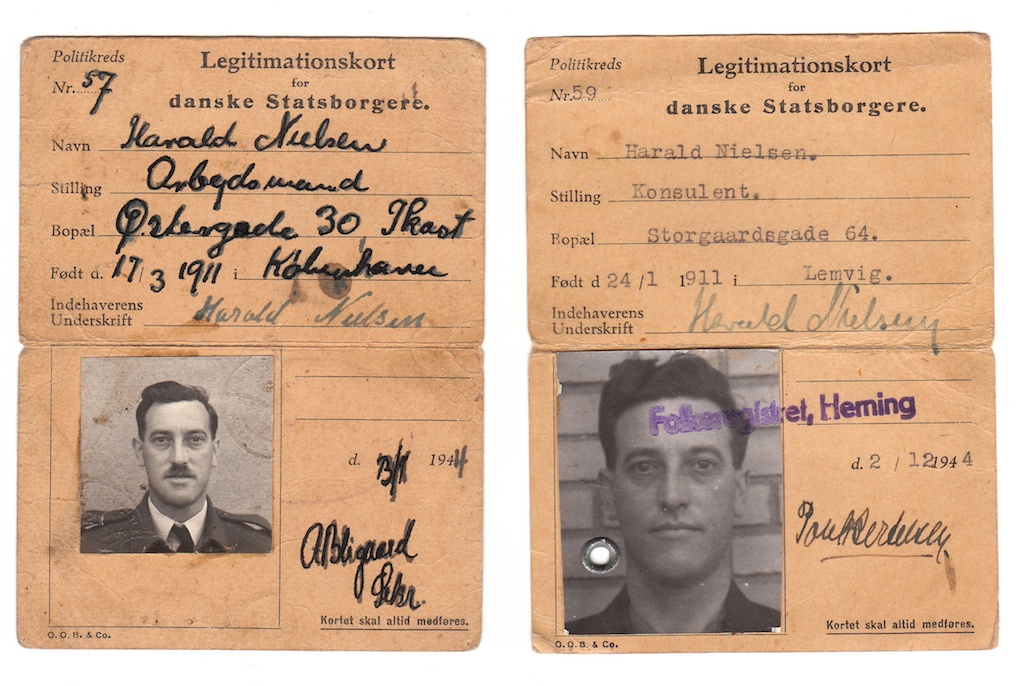

Stoney Mitchell’s memorabilia from his Danish evasion includes two false identity cards, in one of which he is in uniform and wearing a moustache. Clearly he was carrying this photograph when shot down, although it was rather unsuitable for counterfeit purposes in enemy territory as he looks very much like a military man. That card presumably was made on an emergency basis, probably in Ikast, and never used.

Stoney Mitchell’s two Danish identity cards.

The card on the left contains the photograph Mitchell was carrying when shot down over Denmark.

The card on the right contains the photograph taken in Herning against the back wall of Alfred Balle Pedersen’s house.

Original documents in Gail Michener’s personal collection.

The second identity card used a photograph that was one of several taken against the back wall of Alfred Balle Pedersen’s house in Herning. For the Herning photographs, Mitchell met the MI9 advice that “Subjects must look tidy but not ultra smart.” The shirt, tie, and jacket he wore for the photographs presumably were provided by Pedersen, whose several business interests included a clothing factory. A striking concession on my father’s part to conform to Danish norms was his willingness to shave off his moustache, a facial feature that typified his entire life, starting in the mid-1930s when Stoney was articling as a solicitor in New South Wales. Looking more like a Danish civilian was a wise move as Mitchell did have to produce the ID card at a check stop.

The German check stop

After 12 days at the Herning safe house, Mitchell and Bertie were taken by car to Ebeltoft, 135 km to the east. Bertie recalls that, in anticipation of being stopped by a German patrol, “we were briefed on which pocket to keep various things in – eg. our identity card was kept in the inside left pocket of our coat so that if we were stopped and the ‘chief’ put his hand in his inside left pocket, we knew that identity cards were required.” The “chief” was Anton Jensen, better known by his cover name of Toldstrup, which he subsequently used as his post-war surname. Toldstrup was a senior member of the Danish Resistance and chief of Weapons Reception for northern Jutland, but on this occasion he dressed as an officer of the Statens Civile Luftværn. As they were nearing their destination, the car was stopped by German soldiers who demanded identity cards from the driver and the three passengers. Writing in 1947, Toldstrup reported that the “German soldier very soon relinquished the driver’s identity card and mine, which were old and worn, but he kept the other two side by side and carefully compared them, while the second soldier shone the lantern on them. Soon afterwards he handed back the cards and said “Alles gut – weiter fahren!” as was the custom on such occasions, and we continued.”

Mitchell and Bertie safely reached their destination in Ebeltoft, where they were protected for a couple of days by the local custom’s inspector Svend Aage Ballisager whose Resistance work included receiving weapons smuggled from Sweden to Denmark by boat. The two Australians had no further need to produce their identify cards. Finally, on 5 April they were driven by local Resistance members to a Resistance-owned fishing vessel “Freden” which took them to Sweden.

Sources:

The National Archives, UK, MI9 Bulletin: WO208/3268

The National Archives, UK, Bertie and Mitchell debriefing reports: WO208/3327 (-)3093 and (-)3094

M. H. Bertie report 1977 “Experiences in Denmark”, archived in Borge Rasmussen Arkiv, Ringkøbing-Skjern Museum

A. Petersen letter: private collection of Sue Westcott, Blackheath, NSW, Australia

Toldstrup 1947 Uden kamp – ingen Sejr p. 85